What Is a Project Proposal?

A project proposal is a way to present a detailed description of how you or your organization plan to solve a certain problem. It includes a list of activities that should be implemented and the associated costs. Project proposals also highlight why your solution to the problem is the best and why the approver should choose it.

Project proposals provide an outline of what a project will accomplish, what it will deliver, how long it will take, the resources it will use, and the budget it will require.

All project proposals are unique, but use a similar format. They all highlight a problem, a solution, a timetable, and a budget.

Project Management Guide

Your one-stop shop for everything project management

Ready to get more out of your project management efforts? Visit our comprehensive project management guide for tips, best practices, and free resources to manage your work more effectively.

What Is the Purpose of a Project Proposal?

Project proposals are a way to begin formal communication between a person or company and a stakeholder who wants to accomplish something. Often, they lead to the development of a contract or a plan to complete certain tasks. The proposal highlights a solution to a specific need and is a preliminary blueprint to coordinate all of the elements of a project. It provides the structure for what the project will look like and aligns the necessary resources.

“The proposal puts you in line to get new business. Most business that comes into a company comes through a proposal. Proposals are the economic engine for a company,” Harris says. Usually, companies do not just offer new work to other companies. They also need to prove themselves, and that requirement is generally achieved through a proposal process, Harris explains.

Different Types of Project Solicitations

The type of project proposal you submit depends on the type of solicitation to which you’re responding. There are many different types of project solicitations: from within companies, from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), for government grants, from private companies, from foundations, and many others. Each type differs in how they are solicited, accepted, reviewed, and awarded.

Some are formal solicitations outlining what a customer or funder wants. With these kinds of requests, there is usually a request for proposal (RFP), which formalizes the application process and outlines the format of the proposal. For these types of proposals, the submission process is often highly structured.

More informal solicitations for proposals can result from a conversation or some contact between two parties. Sometimes, the process for submitting this type of proposal can be as simple as sending an email attachment.

Other proposals are unsolicited, kind of like making a cold call. Since nobody has asked for them, unsolicited proposals are often difficult to write because there are no specific guidelines for convincing a funder or approver that they need what you provide.

There are also project proposals for renewing, continuing, or supplementing funding:

- Renewal Funding: These proposals make the case for continuing funding after the initial term of the project expires.

- Continuation Funding: After the initial project term expires, sometimes work is not complete. Therefore, companies need more time to use the initial funding in order to either complete the project or start a new phase. This type of proposal outlines these terms.

- Supplemental Funding: These are proposals that ask for additional funds and resources beyond what was included in a previous proposal, either for the purpose of expanding the scope of the project or finishing the initial project. Supplemental funding proposals need to justify why additional resources are necessary, show why the project is still worth doing, and explain why the initial budget was not sufficient.

“What you are trying to communicate is that the value we are going to deliver minus the cost we are going to charge you is greater than the value of any other alternatives minus the cost of that alternative,” he says.

What Are the Different Types of Proposals?

Just as there are different types of solicitations for proposals, there are also different types of project proposals, and they vary by industry. Below are the major categories of proposals:

- Business Project Proposals: Business project proposals come in many different forms. Often, they outline terms for the project and can act like a contract. Business project proposals can be about a project or business idea that one person or company has that would benefit another stakeholder or business. They can be partnership proposals to merge products, events, or development. Business project proposals can also concern a sponsorship, corporate donation, or professional connection that helps one entity provide a good or service.

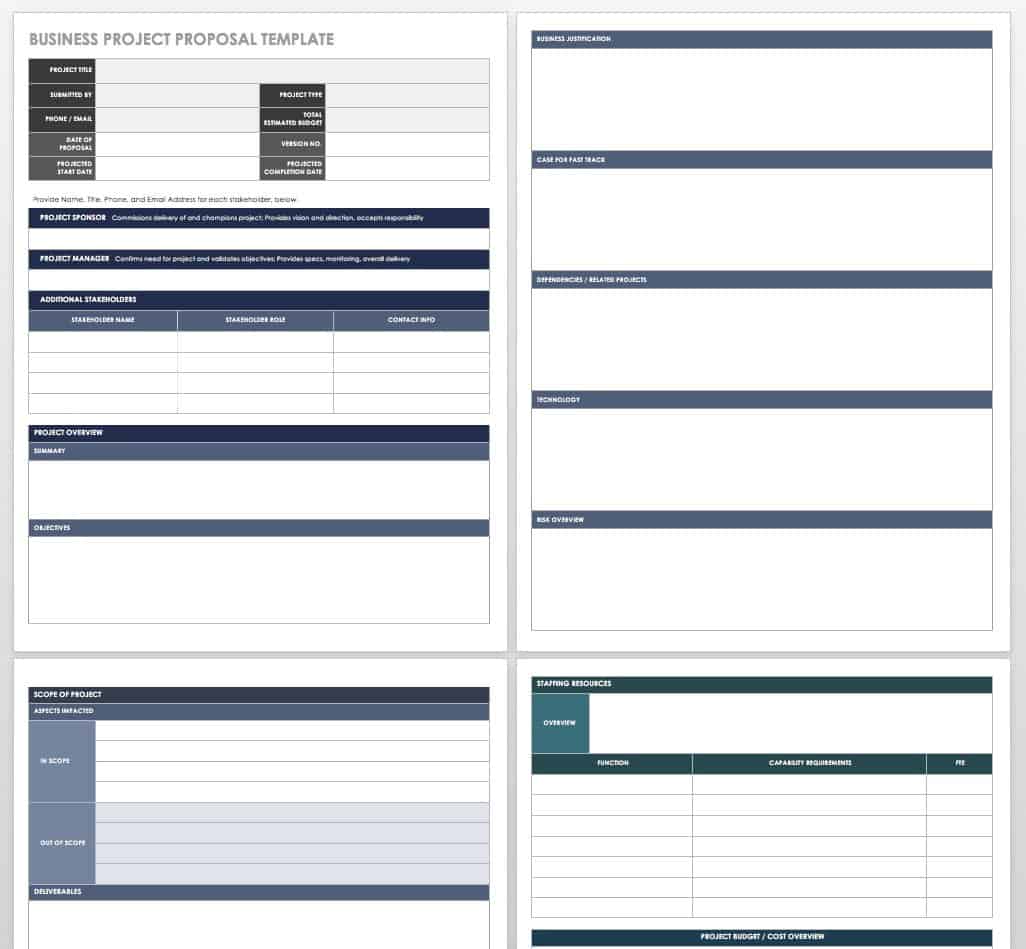

Use this business project proposal template to list project details, objectives, justification for and impact of carrying out the project, and resources required. Additionally, use the built-in timeline to outline your proposed schedule.

Download Free Business Proposal Template - Word

- Engineering Project Proposals: Engineering is a field that relies on details, so engineering project proposals should be detailed as well. Often, these types of proposals are to find new customers, gain new partnerships, obtain new contracts, and gain project approval.

- IT Project Proposals: The key to IT project proposals is to know the audience and the complexity of the project. Sometimes, you need to keep the proposal simple so the reader can understand it. People who are familiar with the IT world might understand more than outsiders would.

- Software Project Proposals: The level of complexity is also an important factor in software project proposals. Often, the writer is trying to convince a business person about why a particular software will help with a task. Give them just enough information, so they understand the problem and the solution you are suggesting.

- Construction Project Proposals: Construction projects are sometimes more formal, especially regarding government projects. In addition to explaining the details and needs of the project, construction project proposals include the name and requirements of the project, the timeline, the necessary workforce, and the cost for completion.

For more information about proposing construction projects, check out this article on construction bidding. - Statement of Work: A statement of work (SOW) is a document that explains the work to be done, why it needs to be done, and why you or your business is the one to complete the work.

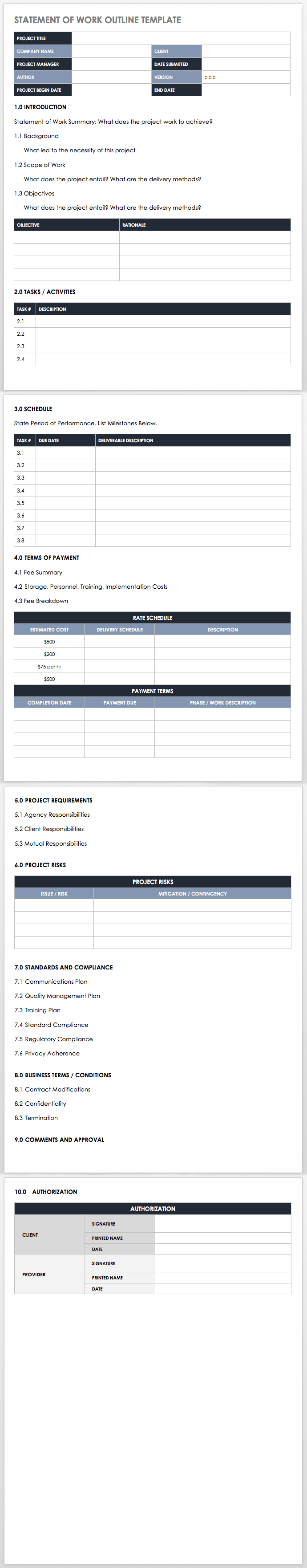

The statement of work outline template below is ready to use in Microsoft Word format, and can serve as a guide for creating your own SOW for your project. Since statements of work differ by industry, you will need to customize yours for your own use. The sections in this template include introductory information, scope of work, tasks, scheduling, and payment terms. For your convenience, there are preformatted tables to make it easy to highlight details. To break up the text and make the document easy to read, you might want to use bullet points in the template sections that don’t include tables.

Here are some additional statement of work templates to ensure you include the necessary information and use the correct format. For more details about writing a statement of work, see this article.

- Research Project Proposals: Many universities, government agencies, and other funders support research projects in a variety of fields. Research project proposals are especially vital to graduate students and researchers in a variety of fields. This type of proposal is an initial document that outlines a study or research project that a person or department would like to perform. It must be realistic, achievable, and appealing.

- Student Proposals: Student proposals are crucial to both students and academic institutions. They outline projects that either a student or group of students wants to do as part of an academic institution’s academic requirements. The projects help students learn and grow academically.

Basics of a Project Proposal

No matter what type of project proposal you are writing, there are some basics to keep in mind: Know your audience and who will be reviewing the proposal. Different people understand different things, and the language and terms you use could impact the approval of your proposal. If someone does not understand the project and what it will accomplish, they are unlikely to approve it.

Everything in the proposal needs a reason to be there. It should be relevant, organized, and stated succinctly and precisely. The RFP or other solicitation should outline requirements and guidelines for proposals. The level of detail varies. For instance, some government grant applications specify the number of pages, the font, the font size, and the size of the margins.

“Read the RFP and respond to the RFP. You have to follow the directions to the letter and make sure you include everything in your proposal,” Harris says. “If you don’t follow the directions, they will reject your proposal.” Harris suggests creating a compliance matrix or chart for each proposal, so you can check off requirements as you meet them.

In general, a proposal should answer the following questions:

- What is the problem your project will solve?

- How does this project align with the organization?

- How does the project benefit the organization?

- What are the project’s deliverables?

- What is the time frame for the project and how do you plan to meet it?

- What resources will you need to complete the project?

- What is the budget?

- How will you measure the project’s success?

- Are there any risks associated with the project and how will you overcome them?

- Who is responsible for the completion of the project?

“The proposal that will rise to the top is the one that focuses on the request, the solution, and how you can help the company that is asking for help,” Harris points out.

Sant has some general guidelines about how to structure a project proposal. He calls his guidelines the “pattern for presenting a solution persuasively.”

What Is the General Outline of a Project Proposal?

No matter what kind of project proposal you’re writing, they all have some common elements , the primary one being that all project proposals are divided into sections. Structuring your document this way shows the reader that you understand the project and know how to execute. Keep in mind that different people might be reviewing different sections.

Depending on the type of proposal or the RFP, the corresponding sections might have different names, but their functions are similar. Basically, the proposal needs to identify a problem, outline a solution for that problem, show why the solution is necessary, provide a budget, and profile who will do the work within a specific time frame.

Here are the basic sections of a proposal (as well as several possible titles for each section):

- Executive summary, project summary, introduction, overview, abstract

- Statement of problem, history, opportunities, project background, challenges, project justification

- Solution, objectives, requirements, project definition, recommended options, methods of activities, narrative

- Budget and costs

- Measurement, tracking, success, reporting, evaluation, monitoring

- Conclusion and appendix

There are so many different potential names for these sections that APMP’s Harris says that his organization has created a glossary of terms. He suggests using the section headings listed in the RFP or creating a standard for your company.

The executive summary section is like an elevator pitch, generally mentioning the problem, solution, and timeline. The purpose of the section is to get the attention of the reader.

The statement of the problem section puts the project and problem into context and shows why the project you are proposing is necessary.

In the solution section, you explain how you will solve the problem. This includes the project’s schedule and methodology.

The remaining sections explain the budget and evaluation methods. The proposal concludes by reminding the reader about the problem and highlighting why you’re the best to solve it.

What Is the Rationale in a Project Proposal?

In the rationale section of a project proposal, you show why you have the best solution to a particular problem. The rationale section is sometimes called the project background because it is where you explain why the project you are proposing is necessary. The section often includes evidence, data, and examples.

This section analyzes the problem, illustrates why your organization understands the problem, and demonstrates why your organization is the best choice for addressing that problem. Sometimes, the rationale even mentions other work being done in the area.

However, don’t spend too much time talking about yourself and your company. “A big mistake proposal writers make is talking too much about their company, its legacy, and what it does,” Harris says, adding that the company reading the proposal is only interested in what you can do for them and at what price.

Sant seconds that opinion: “Proposal writing is a little like courtship. If the person you’re out with talks all about themselves, there probably won’t be a second date. It’s the same with proposals.”

General Advice before Writing a Project Proposal

Writing project proposals is not something to take lightly. Your future might depend on whether or not someone approves or funds your project.

“I think people have come to realize that it’s not enough to submit generic content,” Sant says. He believes proposals really need to be about understanding a client’s needs. “It makes it more persuasive and less of an information dump,” he continues.

Plan ahead for writing a project proposal. Clear your schedule and focus. Know who will be writing the proposal. Will it be one person or several people? Who will edit the final proposal, so it has one voice and a consistent message? Is someone gathering all of the information and data you need?

“The key is organizing before you write. If you organize your thoughts, that goes a long way when writing proposals,” Harris emphasizes. Don’t just cut and paste from other proposals and don’t write just to write. “You need to go into it thinking you are going to win it. Bid on things you can win,” he says.

Gather your resources and know what you need. Set timelines and assign tasks. Be realistic about what you can accomplish and in what time frame. Research the topic you’re proposing. Make sure you know and respect the specific requirements for the proposal, especially deadlines.

Harris says APMP puts out RFPs several times each year and receives many proposals. Often, if a proposal is due at 5:00 pm EST on a Friday, some people turn it in on Monday morning, thinking the deadline is not important. Being late disqualifies the proposal. “You have to be logical. If you miss the deadline for turning in a proposal, why should I think you will meet the deadlines in the proposal?” Harris explains.

When you are almost ready to write, outline the proposal and get peer feedback during this and other stages of writing the project proposal. It’s better to know sooner rather than later if someone does not agree with what you are proposing.

Use headers for the sections of the proposal, since some people pan and scan it. If there are charts, images, or graphs, make sure they look good.

As for the writing itself, be sure to do the following:

- Use clear language and avoid jargon.

- Get to the point and do not make the proposal too complex.

- Define acronyms and have an acronym page if there are a lot of them.

- Use action words like organize, prepare, research, restore, achieve, evaluate, exhibit, offer, lead, involve, engage, begin, compare, reveal, support, demonstrate, define, implement, instruct, use, produce, validate, test, verify, recognize, etc.

Sant talks about writing style by explaining three types of words to avoid: “fluff, gruff, and weasel words.” Sant explains fluff words as the unnecessary words, like game-changing, world-class, synergistic, state-of-the-art, best, uniquely qualified, robust, innovative, etc. “The more you use fluff words, the less the reader trusts you. They don’t mean anything,” Sant says.

Gruff words are the confusing and large words often used in academic and legal documents, and they do not impress a reader. “That’s writing in which the goal isn’t to communicate, but to intimidate,” Sant explains. “We want the writing to be clear. Sentences should be 15 to 18 words. Complicated and complex language communicates complex and complicated projects,” he offers.

Sant says weasel words are the ones writers often use to camouflage uncertainty. That uncertainty comes across to the reader, leaving them to wonder if the project will work or not. Examples of weasel phrases are may, could, and might.

In case different people review different sections of the proposal, make sure each section can stand alone. Don’t assume a reviewer has read all the previous sections of your proposal.

Harris suggests looking for ways to make the proposal visually appealing, like using charts, graphics, timelines, and diagrams.

Think about what success will look like after the project is finished and make sure that positivity gets into the proposal itself.

How Do I Write a Project Plan?

A project plan, also known as a project management plan, is similar to a project proposal. It contains both the scope of a project and the objectives it will achieve. It is not meant to be a day-to-day calendar of tasks, but rather an overall planning tool to keep you and your team on track to achieve the stated end results.

The overall advice for writing a project proposal is similar to that for writing a project plan:

- Research the topic.

- Understand the project and why you’re doing it.

- Outline the plan itself and the timeline to complete it.

- Gather your resources.

- Know what executing your plan will cost.

- Discuss how to measure success and evaluate the results.

Often, a Gantt chart will make it simple for anyone interested in the plan to understand what it will accomplish and how. Check out “How to Create a Gantt Chart in Excel.”

Writing the Sections of a Proposal

Once you have done the research and gathered your resources, it’s time to write the project proposal. Each section has a specific purpose. Keep in mind that there are many possible names for the sections. The RFP or industry standards should tell you which ones to use for your proposal. You might not use all of them, you might combine them, or you might even add additional sections. Here is an overview of the sections in a proposal:

- Executive Summary/ Introduction/ Overview/ Abstract: This introductory section is the place where you get the reader’s attention and win them over. Give them a reason to care about your proposal.

The executive summary section is an overview of the facts. Tell the reader what the problem is, what is currently being done about it, and what your proposal will accomplish. Keep it short and briefly mention your vision for the project and the time frame.

“If you don’t get them in the first 15 seconds, you’re likely to lose. The first paragraph needs to be about them. It needs to say, ‘Here’s what we can do for you,’” Harris says. “Always turn it around to the company you’re talking to. If you’re writing about your company [in the introduction section], it’s a complete turnoff. Turn it around to say, ‘We can help your company achieve its goal of accomplishing x, y, and z,’” Harris explains.

A few good statistics can help you make your case and help the reader connect to both the problem and your solution to it. Remember, this is just an introduction. You will get into details later in your proposal.

This section is not about you or your company. It’s about how you will solve a client’s problem. “It should not start out with, ‘ABC company is pleased to respond to your RFP.’ The first words shouldn’t be your name. They should be your potential client’s name,” Sant says.

If appropriate, it is okay to acknowledge the risks associated with your plan. Also, reinforce that you know what the company, funder, or client is looking for. End the section with a positive statement about how you plan to tackle the problem. - History/The Problem: This is the section where you show your knowledge of the problem and what is currently being done about it. This section needs to be thorough and contextualize the project you are proposing. This is not where you lay out your plans for fixing the problem. That comes later.

Historical data can help provide a solid foundation for your proposal. It will help show the need for your project and the reason you are proposing it.

Through your research, you should know about other projects that either complement or conflict with the project you are proposing. It is okay to mention those projects as part of your industry analysis.

Communicate how your project fits into the organization’s objectives and relate it back to the person reading the proposal. Establish a shared interest in completing your project by making the reader care. - Solution/Objectives/Requirements/Project Definition/Narrative: This is the bulk of your project proposal. It is where you get into the details about what you plan to do and how you plan to do it. In some cases, it is one large section; in others, you may want to divide it into several sections with subheads.

Begin with a narrowly focused synopsis of the project you’re proposing. Show the reason for your project and why your solution is the best way of addressing the problem. Harris suggests highlighting your company’s past successes in solving similar problems. “Show what you did in past projects,” he says.

Talk in detail about what you’re going to do, and explain the deliverables you intend to produce.

“Deliverables have to be linked back to the customer’s needs,” Sant explains. “To just describe the deliverables does not do the job. We have to connect the dots. We have to show [the reader] that this part of our solution will have these results.”

A listing and explanation of your goals and objectives are also part of this narrative section. Goals are broad and define the overall project. Objectives provide the details about how you will reach your goals.

“A goal is the soft thing you would like to accomplish. The objectives are how you reach your goal, the roadmap to your goal,” Harris says. He uses the example of a company with a goal of selling 200 additional magazine subscriptions during a set period of time. The objectives to reach that goal are finding current readers who might like to subscribe, going to trade shows to promote the magazine, partnering with a local newspaper, approaching people who might not know about the magazine, etc.

“Set a goal for everything and really think through your objectives. The objectives are how you reach your goals,” Harris says.

Remembering the acronym SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound) will help you with this section. These reminders will help you create goals and objectives that you can accomplish. For further guidance, see “How to Write a S.M.A.R.T. Project Objective.”

Next comes the timeline, which needs to span the beginning of the project to the end. It is critical to estimate the time accurately and not to underestimate. Make sure to leave room for errors and unforeseen circumstances.

In the timeline, list project phases and milestones and break them down into smaller tasks, albeit not too small. “[Too many steps] might make the project look too complex,” Sant says.

It may be possible to use a Gantt chart for the timeline if the formatting for your proposal guidelines allows it. In order to define necessary steps, get a project manager involved to help you use project management principles.

In this section, assume your client is looking at other vendors or service providers, because, while you need to sell your plan, you don’t want to present yourself as a type of savior (i.e., as the only one who could possibly fix the problem at hand). Acknowledge limits and address risks while showing you’re the best for the job. - Budget/Resources/Costs: This is your opportunity to talk about how much your project will cost and the other resources you will need to complete it. As with all of the other sections, you will need to know the requirements for presenting your budget. Some RFPs require detailed budget breakdowns and narratives explaining them. Others just want a rough idea.

As with the timeline, it is essential to estimate the budget accurately and not to underestimate in the hopes of making your proposal look better than others. Do not forget to include salaries, supplies, indirect costs, equipment, and any other hard costs associated with the project.

Demonstrating value in the pricing section is key. Harris says he has at times accepted higher cost proposals because he felt there was more value attached to what he was getting for the price. “Show the value in your pricing. You can be more expensive than your competitors, but you must demonstrate value. Show me why I am going to be spending more money and what I will get in return,” Harris says.

He also recommends charting out what you will charge. “One number isn’t going to cut it. Leave no mystery as to your final number,” he says. Explain all costs and remember to demonstrate their value to the final product.

In this section, you can also define who is responsible for specific parts of the project. Highlight their responsibilities and qualifications for the project. You’re trying to show the reason for the project and how it offers a good return on investment. - Measurement/Evaluation/Reporting/Monitoring/Tracking: You may think your solution is the best one to fix the problem at hand, but how will you prove it? That is the purpose of the measurement and evaluation section.

Discuss how you will measure the success of your project. Will you collect data as you implement the project and as it progresses? If so, what kinds of data will you collect? How will you interpret that data?

Some RFPs outline specific evaluation and reporting guidelines, so make sure you address them in this section as they apply to your proposal. Government grants have extensive reporting requirements. - Conclusion/Summary: This final section is where you remind the audience why they should approve your proposal. No new information should go into the summary. Rather, it should reassure the reader that you have researched the topic and provided the best possible solution to the problem under discussion.

Summarize the key points of your proposal: what you are going to do, why you need to do it, and how you are going to do it.

How Do I Write a Project Plan?

Writing a project plan is similar to writing a project proposal in the sense that it has several sections outlining what will happen, how it will happen, how long it will take, how much it will cost, and how it will be evaluated. It provides a type of roadmap for a project. Some organizations use the terms project plan and project proposal interchangeably. However, there can be some key differences.

A major difference is that a project plan can change over the course of the project. It is a plan and sets the course, but it can go off-script.

Another difference is that the plan outlines how a project will proceed, and the proposal is a document used to request approval and/or funding for a project.

Here are some other differences between a project plan and a project proposal:

|

Project Plan |

Project Proposal |

|

Geared to mostly internal audiences |

Often geared to external organizations or funders |

|

Used to implement a project |

Used to make funding and resourcing decisions |

|

Focused on impersonal, technical details |

Focused on the need to convince approvers to take action (can include emotional appeal) |

|

Used to explain how a project will happen |

Used to explain why a project needs to happen |

Writing Short Proposals or One-Page Project Proposals

Sometimes, a manager or potential client just wants a brief proposal outlining what you want to do and how you want to do it. Often, this type of proposal comes after a conversation or discussion where one party asks the other for more detailed information about an idea.

These kinds of proposals include the same information as the longer ones, but are presented in a much more succinct format.

Here are the sections to include when writing a short proposal:

- Overview: What is the project you are proposing and why are you proposing it?

- Why You: Show why you are the best person or company for the job. Highlight your past experience and your value. Be honest and excited about the prospect of the project.

- Pricing: In addition to showing how much the project you are proposing will cost, you can provide other options at different price points. People like having options.

- Terms and Conditions: Keep this section simple and not lawyer-like, but include payment terms, intellectual property rights, etc.

- Call to Action: Tell the reader what to do next. Lead them down the path of what you want them to do, which is probably to sign the proposal and begin the project with you.

Before Submitting a Project Proposal

No matter what kind of proposal you write, it is important to get feedback. Look for weaknesses in your arguments and address them before submitting your proposal. Have someone else read it to make sure that it makes sense and that the key points come across.

Here’s an editing checklist to follow:

- Does the proposal follow the required format (sections, font, type size, margins, number of pages, etc.)?

- Does the proposal use language people will understand?

- Does it define terms and acronyms?

- Is there an appendix with supporting documents if one is allowed and necessary?

- Does the proposal address the key motivations of the funder or approver?

If you have questions, some funders allow them before submission. Harris says it’s okay to form relationships with the people issuing RFPs. Do what you can to separate yourself from your competitors.

Submitting or Presenting the Proposal

Once you’ve put in the hard work to research and write a great proposal, you need to submit or present your proposal. With some government grants, submitting involves uploading files to a database and waiting. Sometimes, you just email a proposal to a potential client. Other times, you will need to formally present your proposal.

In general, a proposal should never surprise a client. The submission should come after some initial contact or a request for proposal. In a sense, the document is a summary of your previous contact and conversations.

If you need to present in front of an audience, be sure to do the following:

- Research your audience and direct the proposal to them.

- Be prepared for questions and discussion.

- Prepare a short rebuttal in case the potential client turns down your proposal.

No matter how you present your proposal, make sure you reinforce that you are delivering a value to them, not just selling them a product or service. You have a identified a problem that you think needs a solution, and you are the one to provide that solution.

Education and Training for Proposal Writing

Many medium-sized and large companies have proposal writers on staff who write proposals full-time. Some smaller companies do not have that luxury.

“Most proposal writers will tell you that they fell into proposal writing,” Harris says, adding that he got into it when someone at a former company (who needed to write a proposal) realized that he could write well. Then, he was hooked: “Most people who are proposal professionals will tell you they do it because there is a thrill to the win.”

But, he needed to learn. “You need to know how to write, but you also need to know what to include and exclude,” Harris points out. Business and other schools only touch on the subject, but are starting to add more curriculum about proposal writing. Some universities have writing centers dedicated to helping craft project proposals, since proposals and proposal writing are integral to student research projects.

APMP has sponsored a book called Writing Business Bids & Proposals for Dummies to teach people the basics about proposal writing. The association also has an annual conference in which industry professionals learn from each other about the latest trends and tips.

Three APMP certifications are also available. The level of certification depends on the years of experience in the field and other factors. Harris says certifications are the main reason many of the association’s 8,200 members join. “They want to be known as someone who has credentials to set them apart,” he says.

Even though proposal writers are often the ones to bring in clients to companies, Harris says companies often overlook their significance: “A lot of folks who write proposals are very organized and efficient, but they’re not the ones who stand out in a company, even though they drive sales. It’s an overlooked profession and it’s an overlooked art.”

Execute on Your Project Proposals with Smartsheet for Project Management

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.